August 1st, 2023 · over 2 years ago

Life at the Margin

How I Got $25,000 in Debt

Financing my life with credit cards and margin loans.

“I’m running a negative cash conversion cycle,” I explained, as I picked up the check.

We’d just enjoyed a sumptuous dinner of duck and dumplings at Harborview in San Francisco; the total for eight was $360, so my share was $45.

“If I put it on my credit card, I don’t have to pay it back for 15 months, so happy to take this unless someone else wants the points.”

When I last wrote about my personal finances, four years ago, in 2019, I’d only been working full-time for about six months. I was making good money working in big tech and had about $25,000 of cash to my name.

Four years later, I am excited to announce that my peak income to date was three years ago, in 2020, and I have not held W-2 employment since 2021.

Simultaneously, I now have a little over1

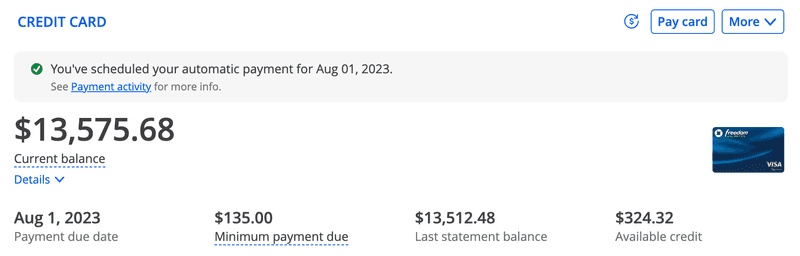

negative $25,000 to my name: $5,000 of margin debt, $10,000 of student loans, and $13,000 of credit card debt (I make the minimum payment every month). As a full-time college student this year, I expect that 2023 will be my lowest income year since graduating high school.

Here’s why getting into debt has been one of the most valuable financial decisions I’ve ever made.

Some caveats

On the number above: while my liabilities exceed $25,000, my assets are now around $100,000 (about $75,000 of which is liquid, mostly in stocks), so my true net worth (i.e. assets minus liabilities) is still comfortably on the right side of zero.

Moreover, while a 25% personal debt-to-asset ratio might seem relatively high, I know that if I really needed to, I could pay all my debt off in a couple of months (e.g. by getting a full-time software job). Instead of seeing the debt as $25,000, I think of it as a few months of work in tech2

Importantly, this debt doesn’t feel overwhelming to me at all. If having this debt really stressed me out, I don’t think it’d be worth it, even if it was economically/financially “optimal.”

× Close.

Finally, all of my debt is from relatively low-interest rate sources, with nominal rates ranging from 0% to 7% (even the credit card debt), while annualized inflation has ranged from 3% to 6% this year.

These conditions — a solid cushion of liquid assets, high future expected income, and access to low-interest rate sources of debt — are not necessarily typical for the average college student, so for the sake of covering my bases with FINRA and the SEC:

This is an opinion and is for informational purposes only. You should not construe this information as legal, tax, investment, or financial advice. This is not a solicitation to buy or sell securities. You should consult your own legal, tax, investment, or financial advisers before engaging in any transaction.

Why borrow?

Since I’m a full-time student now and I pay for all of my living expenses and tuition3

at UCLA, I spend much more than I currently earn4

. Fortunately, I have a lot saved in stocks from my time out of school (the three years from 2019 to 2022 when I was working full-time) so getting into debt wasn’t the only way I could’ve funded my current lifestyle; I could’ve also liquidated my stocks. So why did I decide to borrow?

At the surface level — from a purely financial perspective — borrowing to finance my spending is more tax-advantaged than selling stocks, since there is no realization of capital gains; it enables me to keep more of my net worth in assets that will grow in value and compound. At the same time, with the inflation we’ve experienced over the past few years, my debt has grown extremely slowly in real terms; in fact, pandemic-era Education Department policy has allowed me to enjoy a 0% interest rate on my student debt (now totaling $10,000) for the last two years.

While the financial and tax advantages and political and macroeconomic5

To be completely honest, I don’t think I’m well-versed enough in macroeconomics to know how the current rising-rate regime will affect every single aspect of my financial situation (I first started doing this when rates were super low, and while inflation has been helpful on the debt side, rising rates have had the opposite effect on the assets side, and I’m not sure to what extent these effects have canceled out), but I think I understand enough and have kept my debt at a sufficiently manageable level that I can ignore macroeconomics for the most part.If my life depends on what Jerome Powell says at this or that meeting, I’m probably running too tight of a tolerance.

× Closeconditions have made managing my debt easier, they are not the main reason why I’ve borrowed so much.

1. Consumption smoothing

For one, I am borrowing to smooth my consumption across time periods — assuming a concave utility function, this allows me to achieve a higher standard of living than I would’ve been able to otherwise (given the same amount of total lifetime income)6

Formally, this idea is an application of Milton Friedman’s “permanent income hypothesis” or Modigliani and Brumberg’s “life-cycle hypothesis”.

× Close.

Essentially, I have decreasing marginal returns to consumption. When I’m young and I don’t have that much money to spend, an extra dollar spent on consumption goes further then when I’m older, richer, and have lots of money to spend. In more concrete terms, I get more utility out of eating Chipotle every day than starving myself for a month so I can afford one dinner at Nobu (at the end of the day, it’s just food).

Since an extra dollar spent today, as a poor student, goes further than a dollar spent as a working adult, to maximize utility, economic theory says I should borrow money from my future self and spend it on my current self. While I can’t directly borrow from my future self, I can borrow from other places (like credit card companies and the Department of Education) and my future self can pay it back later, which is close enough7

Even though consumption smoothing is theoretically economically optimal, it is not always actually observed in the data. One hypothesis for why not is liquidity constraints — there’s no bank/fintech company that will let computer science majors borrow, say, $50,000 at low, truly “fair” interest rate, even though they’ll probably end up making $100,000+ once they graduate and are effectively guaranteed to be able to repay the loan.I’m able to resolve the liquidity constraint on my end by turning to more unconventional sources of liquidity (like credit card debt and margin loans).

× Close.

2. Nonfinancial compounding

Second, I am borrowing because the rate of growth of the assets I am obtaining with borrowed funds exceeds the interest rate that I can borrow at8

This is how hedge funds justify borrowing — as long as they can generate investment returns at a higher rate than the interest charged on their loan, they’re in the clear.

× Close. I mentioned above the benefit of keeping my net worth in compounding assets like stocks, but there are other, more compelling9

Specifically, the spread between the expected return of stocks and current interest rates has been increasingly narrowing as the Fed has raised rates, and was never generally that compelling to begin with (I am currently paying 5–6% on margin to get stock returns that have historically averaged 7–9% but can range from something like -50% to +50% — this sounds pretty risky as a pure investment strategy if you ask me!).

× Closesorts of compounding at play here too, besides that of financial capital — such as “social” or “human” capital.

I don’t mean to encourage reducing all interactions to financial terms — just thinking about it through this different lens. From this perspective, for instance, levering up to be able to afford airfare to visit old friends at home and meet new people in unfamiliar places is not only fun, but also starts to make economic sense if viewed as growing the exponential base of Metcalfe’s Law as applied to my personal network (“social capital”, if we want to call it that). Borrowing tuition money to learn math at UCLA is “human capital” investment10

I’m muddling consumption and investment a bit here, but I’ve also come to realize that there’s a surprising amount of overlap between the two, at least while one is young (college is a great example of this).

× Closein ensuring that I apply rigorous, logical, and first principles thinking to as many of my life decisions as I can; good decisions will compound, and when I’m in a position to make more consequential choices, I’ll be able to make them soundly. Paying for the entirety of my Pacific Crest Trail hike with a credit card last year bought me experiences in wild, stunning places that I can see myself returning to time and time again, showed me the process of taking many small steps to achieve a huge goal, and instilled in me the confidence to stand on the side of the road with my thumb out and figure my way out of any situation — changes in mindset that I can see affecting how I approach life in compounding ways for years to come.

Altogether, I believe that the non-financial (e.g. human, social) forms of “capital” accumulated from these experiences — not necessarily quantifiable or captured on any sort of statement or valuation — are not only valuable in themselves, but will compound at a far greater rate than the 6–7% I’m paying in interest11

The true test of this belief would be to ask me the maximum rate at which I would borrow to support these alternative-capital-building activities. Maybe 10–15%?

× Close. I also believe that I’ll eventually be able to turn some of it back into financial capital and pay off my debts while keeping a handsome chunk off the top12

A two-sentence summary of this section (sent to me by a reader) that I really like:“The human and social capital angle is pretty compelling. Most ‘consumption’ that you’re currently engaging in is pretty high ROI if you’re spending time with smart, driven people who can open doors for you.”

× Close.

Why not borrow?

At the same time, with $75,000 of liquid savings, I could’ve easily just sold stocks and lived off of that; according to Mint, my average spending is about $3,000/month (for everything — including rent, tuition, food, airfare, etc.), so this would’ve easily lasted me about two years. My net worth remains positive and I still live relatively frugally, so am I really “consumption smoothing” in the sense of overextending my spending with the expectation of making it all back later?

This is where psychology (or perhaps more charitably, risk management) comes in a bit — on principle, I refuse to dip into13

(I “dip into” my savings to the extent that taking on margin debt collateralized by it is “dipping” into it)

× Closeanything I consider to be “savings” unless absolutely necessary; I sort of treat my $75,000 of stocks as $0 (i.e. not my money).

Treating the $75,000 as $0, I then apply the logic of consumption smoothing and compounding to justify borrowing; the $75,000 I have in stocks resolves the liquidity constraint14

that I would’ve encountered had I tried to implement this strategy when I was starting out from $0. Having the $75,000 cushion also helps me get over some of the psychological barriers I probably would’ve faced going into negative net worth territory.

But then, viewing this strategy holistically, the rationale for doing this seems to functionally come down to a financial justification: the difference between selling my savings to fund current spending versus taking out loans is that in the latter case, the entirety of my stock portfolio (ideally) continues to grow, rather than whatever amount is left as I sell. The linchpin of the strategy thus becomes access to low-interest debt that grows slower than my savings and investments. The argument that the non-financial forms of capital that I’m accumulating now (human, social) compound at a higher rate than stocks perhaps makes me feel more comfortable with 6–7% interest rates versus 7–9% average annual returns in the stock market, but all said, I’m arguably not truly “consumption smoothing” in the sense of spending more than I could right now.

So perhaps this rationalization is all just a trick — financial and psychological sleight of hand. After all, “levered long stocks boosted with credit cards and student loans” sounds a lot more degenerate than “consumption smoothing + non-financial compounding with a solution to the liquidity constraint.” However, what’s important is that thinking of this financial strategy in the second way helped me get over my aversion to borrowing — and more crucially, spending.

By viewing my decision to take out loans as an economically rational choice, I was able to take on a manageable amount of debt that I think will allow me to achieve more both financially — by hopefully pumping my portfolio returns and reducing my tax burden — and more significantly, non-financially — by providing me with the psychological safety to “spend” more15

Had I financed all of my spending by liquidating savings, I think I would’ve been frugal to a fault, given my typical attitude of “savings are not my money”.So to a certain extent, I think I am “consumption smoothing” by tricking myself into spending more than I would have otherwise.

× Closeof my savings on myself (and similarly on activities that will compound in ways that can’t be captured in dollars).

Of course, after overcoming the psychological hurdles of borrowing and spending, doing more of the same is easy — the most difficult part of this strategy might in fact be ensuring that I smooth on the back half; that I don’t let my debt get so large on the expectation that tomorrow will always be more prosperous than today. While I think I am careful enough about my finances to keep things in check, if compounding works out as well as I hope it will, perhaps that will end up being unnecessary.

How to borrow?

I hold three main types of debt (or more generously, “have access to three main sources of liquidity”):

-

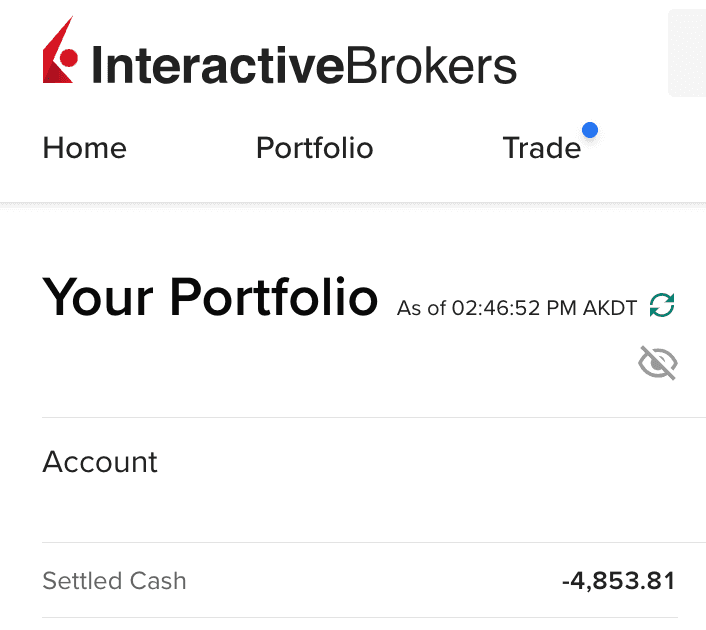

A margin loan, collateralized16

16i.e. Interactive Brokers can sell my stock automatically if I can’t pay back my loan; more on this below.

× Closeagainst my stock portfolio, provided by Interactive Brokers; floating interest rate based on a benchmark (approximately Fed Funds) + 1.5%: $5,000 currently outstanding, have access to up to ~$20,000 more based on how the stock market’s feeling on the given day

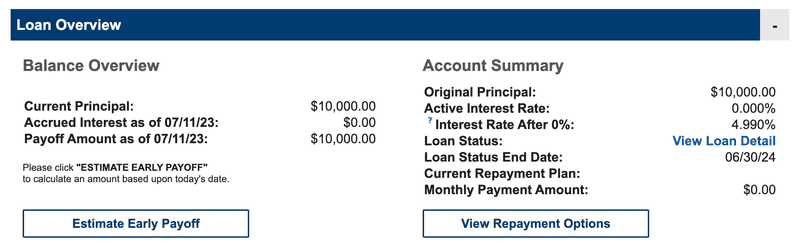

- Student loans, from the U.S. Department of Education; temporary 0% interest rate, after September 2023, a fixed rate based on disbursement date which averages out to about 5%: $10,000 currently outstanding

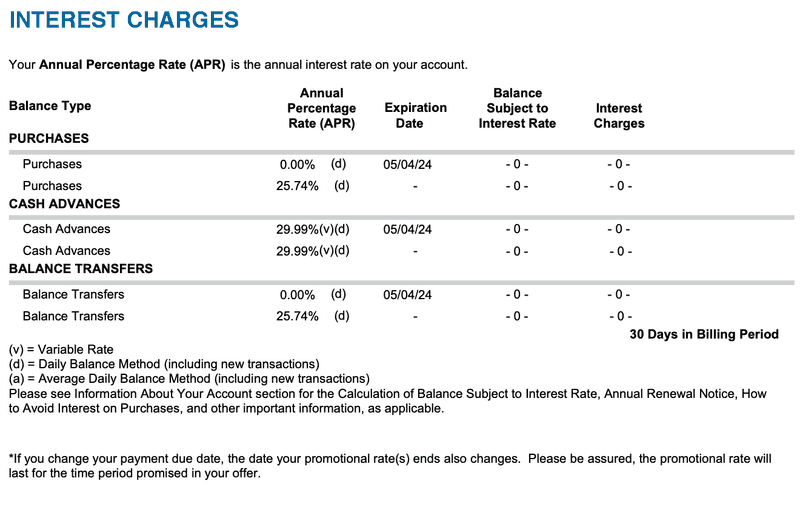

- Credit card debt; 0% intro APR on purchases for first 12–15 months after account opening, depending on card; 25%+ after intro period ends: $13,000 currently outstanding, previously $20,000

Margin loans

In short, a margin loan is a loan taken out against one’s stock portfolio. I first seriously considered taking one out in mid-2021, inspired by a paper called “Life-Cycle Investing and Leverage: Buying Stock on Margin Can Reduce Retirement Risk”. The title mostly speaks for itself, but the authors’ main point is that when one is young, it makes sense to borrow money to buy stocks since stocks always go up17

, and index funds are diversified enough that the risk of it going to zero isn’t as significant as it would be with an individual stock. Essentially, this is sort of like consumption smoothing applied to investing, although I didn’t realize it at the time.

After reading the paper, I tried to implement the authors’ strategy and take out a margin loan myself, but I found that I wasn’t able to do it immediately; I needed to specifically open a “margin account.”

Margin accounts

285 words

Borrowing money to buy stocks is a relatively common tactic among active traders, so many brokerages have an option for customers to upgrade their cash accounts (the default, which only lets the account holder buy stocks with the money they have) to margin accounts (which lets account holders get cash loans from the brokerage to buy more stocks, or withdraw for personal use).

Brokerages charge interest on margin loans, and they collateralize the loan with the account holder’s stock portfolio. This means two things: one, the amount available to withdraw is based on how much the stocks in the portfolio are worth; and two, if the value of the stocks go down and the brokerage thinks the account holder might not be able to pay back their loan, the brokerage has the right to automatically sell their stocks (without necessarily getting their permission first) to pay back the loan. The consequence of this is that if the account holder is not paying close attention, they can lose all their money much more quickly in a margin account than in a cash account. The flip side, though, is that one can make a lot more money more quickly too18

e.g. Let’s say a trader has $100 to invest, and they borrow an additional $100 on margin. Then, they invest the total, $200, into a stock that doubles, leaving them with $400. They still owe $100 on the original margin loan, so after paying it back they have $300. If they’d only invested their $100 into the stock that doubled, they’d have $200. The margin loan allowed them to realize an extra $100 in returns, even though they began with the same amount of starting capital!

× Close.

At the time, I used Vanguard as my brokerage and was mostly invested in Vanguard mutual funds in a non-margin account. I looked into opening a margin account with Vanguard, but found there were two problems with this: first, Vanguard’s margin interest rates are much higher than those of other brokerages; and second, mutual funds can’t even be bought in margin accounts. That meant I couldn’t use my mutual fund holdings as collateral for a margin loan.

Instead, I opened a margin account at a different brokerage, Interactive Brokers19

Referral link if you want to sign up too (I’ll get $200 and you’ll get a deposit bonus based on your deposit amount).

× Close, who are famous for their rock-bottom margin interest rates. I converted my Vanguard mutual fund shares to ETF shares (which was a nontaxable event, thanks to some tax magic on Vanguard’s side) so they could be legally transferred into my new margin account, and then I moved about $50,000 of those shares over to Interactive Brokers through ACATS, a system for automatically transferring securities between brokers.

Soon after the transfer settled in my new Interactive Brokers account, I was able to take out a margin loan of around $30,000 cash (and when I was first setting this up in 2021, the rate offered was 1.6% — 4–5x less than Vanguard). To implement the authors’ strategy, I re-enabled the auto-investment into stocks that I had going while I was employed, even though I was fully unemployed and had no income at the time.

I kept the auto-investment up for a few months and eventually racked up margin debt of $10,000, which was about the limit I was comfortable at against about $50,000 of collateral. Some quick calculations told me that at this level of debt, I’d get margin called and liquidated only if the S&P 500 dropped around 80%, which I figured was a reasonable buffer20

The amount that I’d lose even if the S&P hit that level and I went bust isn’t yet at the level of “life savings”, so that’s another reason why I’m OK with this level of risk. As my savings grow, I’ll probably re-evaluate this, but this post is about me at age 23, not at age 40.

× Close.

Margin was initially pretty scary to me, especially after reading about how margin calls worked, but I’ve always made sure that I have enough of a buffer in my account that I don’t lose sleep over it, and at this point I don’t really think about it. Similar to my 70/30 domestic/international asset allocation in my stocks, I’m thinking I’ll also “rebalance” my leverage21

i.e. the amount I’m borrowing; more precisely, the ratio of how much cash I’m borrowing to how much my stock portfolio is worth.

× CloseAs interest rates have gone up, I’ve gone from paying about $10/month in interest to around $40/month in interest, on outstanding debt balances of anywhere from $5,000–$10,000. This is still quite manageable for me, and having the extra liquidity is well worth it.

Student loans

My accountant wasn’t good enough at gaming the FAFSA23

, so the only type of financial aid I ended up qualifying for at UCLA was a “Federal Direct Unsubsidized Loan.” This is essentially a standard loan with a normal, market-influenced interest rate, except I don’t have to make any payments while I’m in school. Due to the pandemic, the interest rate has been set at 0% since March 2020.

This combination of 0% interest and no repayment until six months after I leave school (upon which I’d presumably get some sort of job) means that this is functionally free money to me. I was limited to $7,500 per year, but I wish I could’ve gotten more!

Credit card debt

This is the type of debt that reasonable people seem to be most unnerved by. Before I began my deep descent into debt, I always paid off my full credit card statement balance every month, and I never considered the interest rate of a credit card because I never thought that I’d ever carry a balance.

When I finally took the time to read the fine print and understand what “0% APR24

Note that a financing offer presented as “0% APR” is not the same as “no interest” — the key distinction being that “no interest” typically has the qualification “no interest if paid in full.”That is, if not paid in full by the deadline, retroactive interest can be charged on a “no interest” offer, whereas with a “0% APR” offer, interest can only be charged on the balance that is left after the intro period ends. This can make a big difference!

× Closeon purchases for 15 months” actually meant, I realized credit card debt was a perfect complement to my margin loans: I could finance most of my spending on credit cards during the 0% intro APR period, carry a balance without paying any interest, and when that ran out I could roll it over into margin debt at Fed Funds + 1.5% at Interactive Brokers — all I needed to do was watch my credit card balances to ensure they didn’t exceed my excess margin liquidity25

(i.e. the remaining amount that Interactive Brokers would let me borrow against my portfolio — based on the value of my stocks)

× Close.

In fact, a month ago I had about $20,000 of credit card debt; $7,000 of it was on a Citi card whose introductory 0% APR expired last month. When the rate expired, I withdrew $7,000 from Interactive Brokers and used it to pay Citi; now the card has $0 on it and I didn’t have to pay any interest for 15 months.

Admittedly, this has had a negative impact on my credit score, dropping it by 30–50 points depending on which report I’m looking at (albeit still above 700), because utilization is such a significant part of the calculation. However, I’m not doing anything right now that requires that great of a score (e.g. auto or home loan), so this doesn’t affect me too much.

The main difference between margin debt and credit card debt is that I can’t directly withdraw cash out of my credit card like I can from my margin account, since the 0% introductory APR doesn’t apply to cash withdrawals. In that way, credit card debt is slightly less flexible than margin debt, but it’s turned out not to have been as much of a limitation as I thought.

“After you Venmo me, I can transfer the cash to my bank account instantly and then invest it until the 0% intro APR period ends next year.”

“Nice, credit card arbitrage, I like it. The check’s all yours.”

- under?↩

- Importantly, this debt doesn’t feel overwhelming to me at all. If having this debt really stressed me out, I don’t think it’d be worth it, even if it was economically/financially “optimal.”↩

- (thankfully, in-state)↩

- (mostly from doing contract software development)↩

- To be completely honest, I don’t think I’m well-versed enough in macroeconomics to know how the current rising-rate regime will affect every single aspect of my financial situation (I first started doing this when rates were super low, and while inflation has been helpful on the debt side, rising rates have had the opposite effect on the assets side, and I’m not sure to what extent these effects have canceled out), but I think I understand enough and have kept my debt at a sufficiently manageable level that I can ignore macroeconomics for the most part.If my life depends on what Jerome Powell says at this or that meeting, I’m probably running too tight of a tolerance.↩

- Formally, this idea is an application of Milton Friedman’s “permanent income hypothesis” or Modigliani and Brumberg’s “life-cycle hypothesis”.↩

- Even though consumption smoothing is theoretically economically optimal, it is not always actually observed in the data. One hypothesis for why not is liquidity constraints — there’s no bank/fintech company that will let computer science majors borrow, say, $50,000 at low, truly “fair” interest rate, even though they’ll probably end up making $100,000+ once they graduate and are effectively guaranteed to be able to repay the loan.I’m able to resolve the liquidity constraint on my end by turning to more unconventional sources of liquidity (like credit card debt and margin loans).↩

- This is how hedge funds justify borrowing — as long as they can generate investment returns at a higher rate than the interest charged on their loan, they’re in the clear.↩

- Specifically, the spread between the expected return of stocks and current interest rates has been increasingly narrowing as the Fed has raised rates, and was never generally that compelling to begin with (I am currently paying 5–6% on margin to get stock returns that have historically averaged 7–9% but can range from something like -50% to +50% — this sounds pretty risky as a pure investment strategy if you ask me!).↩

- I’m muddling consumption and investment a bit here, but I’ve also come to realize that there’s a surprising amount of overlap between the two, at least while one is young (college is a great example of this).↩

- The true test of this belief would be to ask me the maximum rate at which I would borrow to support these alternative-capital-building activities. Maybe 10–15%?↩

- A two-sentence summary of this section (sent to me by a reader) that I really like:“The human and social capital angle is pretty compelling. Most ‘consumption’ that you’re currently engaging in is pretty high ROI if you’re spending time with smart, driven people who can open doors for you.”↩

- (I “dip into” my savings to the extent that taking on margin debt collateralized by it is “dipping” into it)↩

- i.e. if I was the average college student with negative assets and no income, I don’t think there’s any bank that’d give me an unrestricted $30,000–$50,000 line of credit at Fed Funds + 1.5% like Interactive Brokers does.↩

- Had I financed all of my spending by liquidating savings, I think I would’ve been frugal to a fault, given my typical attitude of “savings are not my money”.So to a certain extent, I think I am “consumption smoothing” by tricking myself into spending more than I would have otherwise.↩

- i.e. Interactive Brokers can sell my stock automatically if I can’t pay back my loan; more on this below.↩

- Not financial advice↩

- e.g. Let’s say a trader has $100 to invest, and they borrow an additional $100 on margin. Then, they invest the total, $200, into a stock that doubles, leaving them with $400. They still owe $100 on the original margin loan, so after paying it back they have $300. If they’d only invested their $100 into the stock that doubled, they’d have $200. The margin loan allowed them to realize an extra $100 in returns, even though they began with the same amount of starting capital!↩

- Referral link if you want to sign up too (I’ll get $200 and you’ll get a deposit bonus based on your deposit amount).↩

- The amount that I’d lose even if the S&P hit that level and I went bust isn’t yet at the level of “life savings”, so that’s another reason why I’m OK with this level of risk. As my savings grow, I’ll probably re-evaluate this, but this post is about me at age 23, not at age 40.↩

- i.e. the amount I’m borrowing; more precisely, the ratio of how much cash I’m borrowing to how much my stock portfolio is worth.↩

- (although as I mentioned above, I’ll probably want to reduce my overall leverage as I get older)↩

- (kidding — I fill out my own FAFSA)↩

- Note that a financing offer presented as “0% APR” is not the same as “no interest” — the key distinction being that “no interest” typically has the qualification “no interest if paid in full.”That is, if not paid in full by the deadline, retroactive interest can be charged on a “no interest” offer, whereas with a “0% APR” offer, interest can only be charged on the balance that is left after the intro period ends. This can make a big difference!↩

- (i.e. the remaining amount that Interactive Brokers would let me borrow against my portfolio — based on the value of my stocks)↩

- I keep track of the exact date with a calendar event but generally don’t worry about it.↩

Recommended Posts

If you liked "Life at the Margin: How I Got $25,000 in Debt", you might also like: