August 20th, 2019 · over 6 years ago

4320 Minutes

How I Handled My Suspension on the Common App

Why I took three unplanned days off of school the summer after my freshman year. Handling my high school suspension during the college admissions process and beyond. Thoughts four years later.

I got suspended, ooh, you got suspended

For chiefin’ a hunnid blunts, 14,400 minutesChance the Rapper, “14,400 Minutes” (2012)

Those who have already gone through the college application process — myself included — know that the most daunting challenge emerges in the written section. For many, the biggest test is the infamous 650-word personal statement, and the “background, identity, interest, or talent that is so meaningful they believe their application would be incomplete without it.” There’s another written prompt, however, that gets much less attention — mostly because the vast majority of people have no need to answer it. It reads:

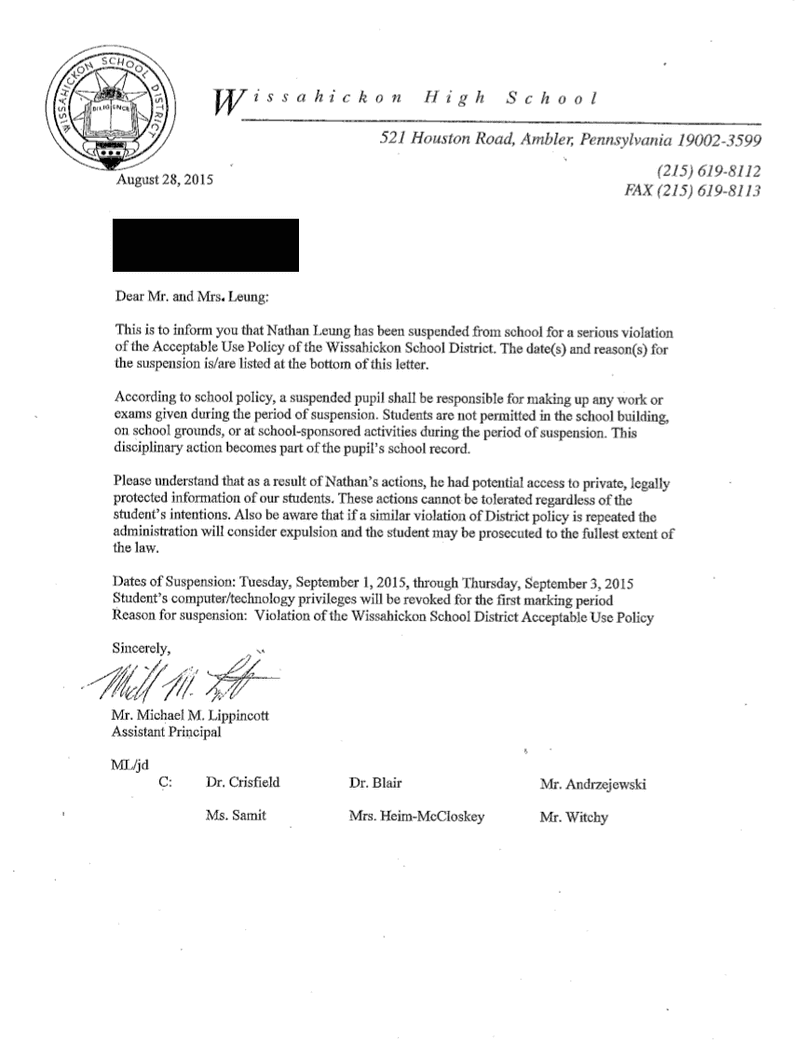

Have you ever been found responsible for a disciplinary violation at any educational institution you have attended from the 9th grade (or the international equivalent) forward, whether related to academic misconduct or behavioral misconduct, that resulted in a disciplinary action? These actions could include, but are not limited to: probation, suspension, removal, dismissal, or expulsion from the institution. If yes, please give the approximate date(s) of each incident, explain the circumstances and reflect on what you learned from the experience.

It was the fall of my senior year of high school, and I had been pondering the question for a few days now. I knew I could answer a glib “no,” and nobody would know any better. But I knew that I should tell the truth. Of course, it was the right thing to do, but I also felt that the “incident,” as the prompt called it, was a formative part of my high school experience. It had been almost two and a half years since, but I still remembered it with remarkable clarity.

Summer was drawing to a close, and seeking purpose out of those lackadaisical last days, the students of Wissahickon High School were eager to return to class. Much more eager, I think, than in years past, which was why I was having the meeting.

It was a late August morning and I was running with the cross-country team, readying for my sophomore season.

“What’s the meeting about?” my training partner asked, between rhythmic breathing.

“I think they might be mad that everyone’s calling in and trying to switch into their friends’ classes.” I replied.

Usually, after summer practice, I would go straight home, but this time, I headed to the main office. The office secretary led me to a darkened conference room. I entered and was greeted by the faces of the assistant principal, the head of the technology department, and the newly hired principal — an imposing, surprisingly tall woman — all waiting expectantly. This was the first time I had seen her, and her unwavering intensity stood in stark contrast to the casual, informal demeanor of her long-tenured predecessor.

“We’ve heard that you’ve been stealing confidential student information,” she declared, her gaze focused intently on my face, “and we’re considering getting the police involved.”

“I’m sorry, what do you mean?” I asked. The room grew cold, and an hourlong interrogation began.

“Were you purposely emulating the design of the student information page?”

“Not at all, ma’am.”

“Why were you collecting student passwords?”

“I saved them first but then deleted them after I used them. I don’t have any of them anymore.”

“Then how did you collect so much information?”

I looked around the sea of hardened faces, all expecting the worst, and struggled to come up with a coherent answer.

“I really don’t know, people just gave it to me.”

Shaken by the principal’s initial allegation, I was attempting to answer as truthfully as I could. I didn’t believe I had done what she was accusing me of, but I could tell my answers weren’t changing her view. I felt powerless.

At the end of the meeting, the principal knew one thing only: I had broken the rules. The committee adjourned and I was left in the room alone with the assistant principal. He smiled, weakly.

“It was smart, kid, but the rules are the rules.”

As I stared at the prompt on the screen, the prompt stared back, accusatory. I struggled to make positive meaning of my experience. Perhaps more accurately, I struggled to make some sort of positive meaning out of my experience in a way that would show I learned something. Of course I had to have “learned” something — the prompt plainly asked for it! All I remembered, though, was that I felt like I didn’t know what I had done, and that I had broken a rule because I didn’t communicate my intentions well enough. After the principal had so ruthlessly questioned me, I felt that her impression of my actions had not shifted in the slightest. In her view, from the moment I stepped into the room, there was no question that I had done something wrong.

This was a college application, though, so I had to say something. I scoured my thoughts for something usable. Research led me to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, a federal law passed during the Clinton Administration which mandated certain privacy requirements for healthcare records. Reading about it, I understood how it could relate to my alleged crime — working with patient data is generally off-limits without some sort of prior authorization and legal approval, and similar logic could apply to student data. I believed it.

After a few more days of writing, I had a seemingly thorough and well-researched response. I showed it to a few teachers, and they thought it was pretty good. That made me feel better about what I had put together, but still, I felt as if something was missing — as if my meeting with the administration was only half the story. To me, the conversations I’d had with fellow students were just as important, if not more.

My first day of school was actually the fourth, after my three-day suspension. My annoyance at the perceived unfairness quickly dissipated as I began the best first day of school in my entire academic career.

“Yo, you’re the kid that made the app, right?”

Initially confused, my lips turned to a smile as I exchanged a fist-bump with a passing stranger.

The “app” was the “incident.” About two weeks before the start of classes, the school released individual class schedules on the student information system. Students would take pictures of their schedules on their phones and send them to their friends, so they could see if any courses matched. It was a tedious process, so I built an app which students could log into with their student information system username and password. When a student logged into my service, the backend would subsequently perform an automated login to the actual student information system with the student’s credentials, download their schedule, parse out the classes, and aggregate the student’s enrollments with the existing rosters I had for the classes in my database. As more students logged into my service and as it parsed more schedules, my class rosters would grow more complete.

By the time I had the meeting, about half of the student body had signed up for the app. It had spread virally on social media and received over 7,000 hits by the time I was told to take it down.

One afternoon a few days earlier, I was watching the numbers go up on my analytics dashboard. As the hit counter went from the hundreds to the thousands and climbed higher still, my phone lit up. I read a message from one of my friends.

“I recently changed my schedule, can you refresh my classes on your app?”

This was an interesting technical problem. I tried to be conscious of efficiency when writing the application, and one way I did that was to only parse each student’s schedule once — on subsequent logins, I would simply check against the student information system to see if the provided username and password were valid credentials for the student, and then pull the existing data I already had. Of course, I could have stored the username and password the student provided initially, but I felt — perhaps presciently so — that this would be a bad idea. Regardless, refreshing an existing user’s classes would require some careful maneuvering in the database.

I was soon distracted by another message, this time from an upperclassman known for his computer science expertise. “Hey man, I’m taking a class with a slash in its name and it’s not showing up on the app. I think you’ve got an issue with your special character handling.”

I noted the bug report, and then switched to the worldwide dashboard to see my global traffic. I’d received hits from Jamaica — somebody must have been checking who their future classmates were while they were enjoying their last few days of summer vacation!

I was amazed. I’d put this together in a few days after cross-country practices, and now, just a few days later, it was looking like I needed to hire a support team for my international user base.

I was unsure how to incorporate this side of the story — the student’s side — into my response. I figured that for the purposes of college admissions, my motif should be — and really, could only be — contrition. The challenge was that the prompt’s focus, the reason I even had to write it in the first place, was my suspension, but I felt there was so much more to what I had done than its unfortunate result.

Significantly, the app was my first major technological success. I had learned to code just the year before, as a freshman, when twenty percent time — an idea popularized by Google, in which their employees can spend one day every week working on their own projects — was making its way into the educational realm. In English class, we were given the opportunity to spend one day a week for eight whole weeks learning whatever we chose to, provided that we blogged about our progress. Perhaps fatally, that same year, the school administration had mandated that teachers use a new learning-management system which was unintuitive, glitchy, and despised by students and faculty alike. That provided all the impetus I needed to decide I wanted to learn how to code and build apps. I challenged myself to make a better platform for my teachers than what the school was providing. At the end of eight weeks, I had made a valiant, albeit rather rudimentary, attempt — but crucially, I learned a lot in the process.

That summer after freshman year, when the following year’s schedules were released, I again saw an inadequate system. It took ninety seconds and a bunch of taps to get my initial schedule from the student portal, and then another few hours or so to wait for all my contacts to get back to me with their schedule. Then, it would take some more time to compare schedules, and by the time I figured out I had class with one person, I’d forget which class I had with another. It was a mess.

Seeking a way to streamline the process, I realized I possessed the skills to make the process better. Using technology, I could decrease the initial time to access my schedule by an order of magnitude and crowdsource other student’s schedules so the comparisons could be done by a computer instead of manually.

That year, schedules were released in the second week of August. I launched the app three days later.

It was great to be the most popular kid in school for those first few weeks of tenth grade, but eventually, as with all things, people forgot. Of course, next August, there were a few jokes about relaunching the site, but I’d learned my lesson — or perhaps more accurately, the lesson that the administration wanted me to learn — and we were back to looking at screenshots again to see who was in our classes. The August after, however, I knew I couldn’t simply laugh it off. It was time to apply to college, and the Common Application pressed me for details.

My response should not have been so hard to write. Over the past two years, I’d thought about the incident and explained it too many times to count, and in retelling the story, people had asked me a great deal of thoughtful questions which should have provided me with great material to start with.

For instance, were students aware of the potential scope of information they were giving away? Most students used the student information system mostly for classes and grades, but there was a lot of other information on it, like addresses, absences, and parent information, and it’s very likely that some students who signed up for my app weren’t aware of the extent of the information they were possibly sharing.

Yet, in my mind, that wasn’t important. The primary reason for the virality of the app was that those who knew me well — who I shared the app with initially — knew me as someone who did things with integrity, and as someone who wouldn’t use their passwords for anything more than what I said I would — to get their schedules. They didn’t have to worry about the other information I could access because I simply wouldn’t access it. Crucially, they trusted me enough to share the app publicly with their own friends, who didn’t necessarily know me. Without this basic level of trust, the app wouldn’t have grown any bigger than my own personal class schedule.

Another question I was asked often was why I was suspended if I claimed to not have hurt anybody. From what the administration communicated, it had to do with the fact that I could potentially have saved users’ passwords and used them for malicious purposes later. Even though I didn’t, the fact that I could have made what I did a dangerous game to play.

Yet, more so than anything to do with technology, I think the administration’s decision to suspend me instilled a sort of tacit acknowledgment in my mind that some institutions are simply inflexible, beholden to more powerful or compelling whims. In my view, the app was a valuable service for the student body, and I felt that I could’ve even partnered with the school to make it more widely available. The administration, on the other hand, likely acting on a parents’ complaint, probably felt it was better to nip my idea in the bud than to let me rework its internals to account for their privacy concerns — which, in my mind, would’ve been a much more instructive experience for everyone. By doing so, the administration, instead of having to explain why they didn’t do anything to that concerned parent, could say that the situation was dealt with and disciplinary action was imposed.

This same feeling of fickle institutional power that came over me as the college process began. My friends were all busy with SAT prep classes, college consultants, and the cost-benefit analysis of applying Early Decision, and I felt like a contestant in a huge, incomprehensible game. Determined to play my cards well, I resolved to do what I was “supposed” to do, and what I had been doing since the “incident.” I maintained good grades, scored well on standardized tests, and participated in varied extracurricular activities. The last thing left to do was to explain my suspension away. All I had at the time, though, was what my teachers had given a stamp of approval for: contrition and “learning.” So, that was what I sent.

Yet, I felt incomplete leaving out an entire — and in my mind, integral — part of the story. That feeling of incompleteness was only heightened when news broke in March that data-mining firm Cambridge Analytica had gained unauthorized access to the data of over fifty million Facebook users. The information was ostensibly collected voluntarily as part of a “personality test” app given to users, but in reality, Cambridge Analytica was scraping the profiles of users’ friends without consent, and using that data for nefarious, unauthorized purposes. I felt eerie connections to what I had done. These apparent parallels were made even more concerning since data privacy, over the past few years — and especially with the recent news — had come to the forefront of users’ concerns, and invasive practices — as varied as the Amazon Echo’s constant listening to Twitter’s influence over the candidates we vote for — had fomented major backlash against Silicon Valley.

My most pressing concern, however, was that perhaps, having only heard half of my story, someone could conclude that what I had done was no different than what these tech companies — Facebook, Amazon, and Twitter — had been so vehemently criticized for. I sincerely hoped that this was not the impression that I had communicated in my response.

Nonetheless, it’s true that many of these companies, like my app, were founded with innocent aims. Facebook wasn’t built with the intention of facilitating foreign influence in our elections — it was built to connect college students. By the same token, Amazon started as a small online bookshop, not a multibillion dollar behemoth swallowing entire industries. Perhaps, if my app grew as large as those companies, I could fall prey to such a Faustian bargain, sacrificing my noble mission for something more sinister — and maybe this was what the administration was trying to deter, seeing my app as a microcosm of the controversies surrounding Big Tech.

However, I think the administration neglected the innocence of that early, pure stage of creation, when Mark Zuckerberg and his friends simply wanted to meet the students in the other houses and Jeff Bezos just wanted an easier way to buy books. They neglected that as Facebook and Amazon were subject to intense media scrutiny, the fiercely mission-driven disrupters Lyft and Airbnb were increasing their philanthropic efforts in the communities they were active in, and doing more to acknowledge the transformative effect — in both good ways and bad — they were having on modern life. Most importantly, I think the administration neglected to consider the nuance — that despite what the news was saying, technology could be a tool for amazing positive impact as much as it could be a tool for surveillance and manipulation.

Regardless of what the administration thought, and more importantly, whatever the impression of the college admissions committees, the response I sent seemed to work, and I committed to attend the University of Michigan that April.

Even so, I still felt that gnawing sense of incompleteness. I felt silenced, sharing only one half of the story while omitting the crucial, and in my mind, incalculably more consequential half — one whose conclusions superseded much of what the other half preached. I yearned to put to paper the full story of what had happened, if not for the Common Application, for me.

Here it is.

Recommended Posts

If you liked "4320 Minutes: How I Handled My Suspension on the Common App", you might also like: