September 27th, 2021 · over 2 years ago

Accredited Investor

Investing in Startups With the Series 65

From studying for the exam to registering with the SEC — my foray into investing in startups and venture capital by passing the Series 65 and becoming a licensed investment adviser representative.

Editorial Note: Between July 2021 and January 2023, I was able to use my Series 65-based accreditation to make minor investments in a small number of startups and venture funds.

In January 2023, the SEC (after conducting an examination of my advisory business) determined that I was actually ineligible for registration under the internet adviser exemption.

Per the Commission’s recommendation, I filed Form ADV-W to withdraw my firm’s registration. I also filed Form U5 to terminate my individual registration. As a result, I am no longer an accredited investor.

In the interest of full transparency, the text of the article below remains the same as before. However, I emphasize once more that this article is not legal (tax, investment, financial, etc.) advice. Consult your own legal (tax, investment, financial, etc.) advisers if you have questions or concerns about this method of becoming an accredited investor.

Wintry air blew through the room and over our table, ruffling our napkins. We’d left the door open as a precaution.

It was December 2020, and I was grabbing lunch at Princeton with a friend (he was back in school after a gap year in San Francisco), catching up on what we’d been up to since we’d last seen each other in the city — almost a year ago by that point.

“I’m looking to start angel investing in startups soon,” he said, in between dumplings.

“Don’t you have to be rich to do that?” I asked.

As an early startup employee, I was interested in eventually getting into investing, but I knew I couldn’t do it legally. I was skeptical that any other college student could do it legally either — there was no way my friend was an “accredited investor.”

What is an accredited investor?

336 words

Historically, the SEC only allowed individuals with a high net worth or income, called “accredited investors,” to invest in risky assets like startups, venture capital, hedge funds, and private equity.

These types of investments aren’t SEC-registered and don’t come with the “protections” of SEC registration like quarterly reporting and strict disclosure requirements, which are designed to make sure retail investors aren’t defrauded.

The SEC’s logic was that if someone was already rich, they would be sophisticated enough to assess the risks and rewards of a risky proposition and make a reasoned investment decision; in the event of a total loss, they’d be able to fend for themselves.

The exact financial qualifications that the SEC uses to determine if someone is an “accredited investor” are:

- earned income that exceeded $200,000 in each of the prior two years, and reasonably expects the same for the current year, OR

- has a net worth over $1 million (excluding the value of the person’s primary residence)

For those who work in tech, these numbers might seem low1

Another reason why these numbers may seem “low” is that the income and net worth figures were established in 1982 and haven’t been adjusted for inflation since. Making $200,000 per year in 1982 is equivalent to making $560,000 per year in 2021.

× Close, which is why so many people seem to be angel investing nowadays (for instance, many young founders qualify — because a 21-year-old CEO who owns 20% of a company that investors have valued at $10 million is technically accredited). Still, these numbers are a far cry from the average college student’s financial circumstances. I was (and still am) not close to qualifying on either financial metric.

My friend explained to me that the SEC had amended the definition of accredited investor a few months prior, in August. They had added another method of qualifying that didn’t involve financial resources at all.

The Securities and Exchange Commission today adopted amendments to the “accredited investor” definition, one of the principal tests for determining who is eligible to participate in our private capital markets.

[…]

The amendments to the accredited investor definition in Rule 501(a):

- add a new category to the definition that permits natural persons to qualify as accredited investors based on certain professional certifications, designations or credentials or other credentials issued by an accredited educational institution, which the Commission may designate from time to time by order. In conjunction with the adoption of the amendments, the Commission designated by order holders in good standing of the Series 7, Series 65, and Series 82 licenses as qualifying natural persons.

SEC.gov, “SEC Press Release 2020-191” (emphasis added)

In short, one could now become accredited, regardless of financial means, if they held one of three financial licenses “in good standing”: the Series 7 (license for public securities brokers), the Series 65 (license for investment advisers), or the Series 82 (license for private securities brokers).

All three licenses could be obtained by passing a multiple choice exam. While the Series 7 and 82 required a firm sponsor, the Series 65 required no such sponsorship.

My friend, without a firm sponsor, was thus studying for the Series 65 exam to get his accreditation.

“You should try and become accredited too,” he suggested.

After lunch, he shared a Google Drive folder with a bunch of study resources with me and added me to a group chat with a few other college students that were studying for the test as well.

When I got home, I started doing some more research. I found that for the exam-based route of qualification, becoming accredited involved more than just passing the test. They key phrase in the SEC amendment is “good standing”. According to NASAA, the organization that developed the Series 65 exam, in order for an individual who passes the Series 65 to be in “good standing” they would:

also need to be licensed as an investment adviser representative in her state and would need to comply with all state-specific licensing requirements (e.g., paying dues, etc.).

NASAA.org, “Exam FAQs”

My path to accreditation now had two steps:

- Pass the Series 65.

- Become a licensed investment adviser representative in my home state, California.

In July 2021, eight months after that first conversation over lunch, my California investment adviser representative license was finally approved, and I am now able to legally make investments in startups and venture capital.

Here are the details.

This is an opinion and is for informational purposes only. You should not construe this information as legal, tax, investment, or financial advice. This is not a solicitation to buy or sell securities. You should consult your own legal, tax, investment, or financial advisers before engaging in any transaction.

I. Passing the Series 65 Exam

Studying for the Exam

I started studying for the Series 65 exam shortly after the lunch in December.

First, I read through the Wiley Series 65 Exam Review 2016 book, which was one of PDFs we had in the Google Drive. I read a few chapters per week, did the practice quizzes after each chapter, and finished the book by January. Because it was the 2016 edition, the book didn’t reflect 2017 Trump tax cuts, and there were a concerning number of typos and mistakes in the answer keys.

Regardless, it was still a passable primer to the topics covered on the test, and importantly, it was helpful in pointing out (at a high level) the exam categories I was weakest in.

For those (like me) who come into the Series 65 with the typical knowledge that someone casually interested in business and investing picks up without formal training — a rudimentary understanding of accounting and a decent familiarity with the mechanics of stocks and bonds — my major weaknesses were in:

- Investment adviser firm compliance (e.g. how many years do you need to keep client confirmations?)

- Securities law (e.g. how many unaccredited investors can invest in an offering of unregistered securities?)

- Trust and estate planning (e.g. what is the difference between a charitable remainder unitrust and a charitable lead unitrust?)

For these topics, I read a bunch of Investopedia articles to supplement the content in the book.

After finishing the Wiley book, I started taking practice exams from another PDF my friend had uploaded into the Google Drive folder. I was scoring decently well (in the eighty percent range — a passing score is 72.3%), so after a couple more solid practice exam results, I created a FINRA test enrollment account and paid the $187 fee to register for the exam.

Upon registering, I was given a four-month window to schedule an exam at a testing center. That meant I had until the first week of May to take the exam, or else I would have to pay the fee again.

I continued taking practice exams from the PDF, and a few exams later, still scoring well into passing territory, I went onto Amazon to look up the actual book that the exams had come from to see if I could find more practice materials. Unfortunately, I found that the actual source of the practice exams, the 2018 edition of Coventry House Publishing’s Series 65 Exam Practice Question Workbook, had extremely poor ratings.

“Practice Exams do NOT allocate questions like actual Series 65” read one review.

A little concerned now, since I’d already paid the $187 registration fee, I began looking for another source of practice materials. Based on what I was reading online, the Kaplan test bank seemed like my most promising option, but the cheapest subscription cost $159, and I wasn’t looking to drop that sort of money given how far I’d already gotten on free resources.

At the same time, other pursuits started taking up more of my time, and I deprioritized studying for the exam. I got a new job, and the four-month test window became three months, then two, then one.

In April, with two weeks remaining in the testing window and no clear plan for the exam other than winging it, I went on a work trip to Miami. At one of the company-sponsored happy hours, I happened to run into someone else who was also studying for the Series 65 (they were working on a fintech company). We were chatting about our study process when they mentioned they had a Kaplan subscription.

“Why don’t you borrow it? I’ll send you my username and password.”

“That’d be awesome, thanks so much!”

This was exactly what I needed.

Later that week, back from Miami, with just a few days left in the testing window, I logged into the Kaplan Series 65 question bank and took a practice test. I scored a 96/130, or 73.8%. This was significantly worse than how I was doing on the practice exams from the Google Drive, but it was still two questions above passing, 94/130.

I can actually pass this thing, I thought, and I’m not in as bad of a spot as I thought I was.

The Kaplan practice test gave me a summary of my weakest categories, so I started doing randomized 20-question quizzes in those categories from the category-specific question banks. I picked things up pretty quickly, and after a few more rounds, I felt confident enough to pick a test date.

I registered to take the exam on May 1st, four days before my window closed.

Taking the Exam

On test day, I took the train up to the testing center I’d selected, an office building just off of Broadway in Midtown, about twenty minutes from my apartment in the East Village.

As instructed in the confirmation email, I arrived thirty minutes before my scheduled exam time. Once I got up to the actual testing center on the 25th floor, I checked in and an employee gave me a plastic bag and a locker key. I was directed to place all of my electronics in the bag and to stow my belongings in one of the lockers provided outside the testing room.

There were about twenty other people in the staging area waiting to get into the testing rooms, so after putting everything away, I got into the line that had formed. As we entered the main testing area, they split us up by exam type — in addition to FINRA exams (the Series 7, 63, 82, etc.), people were taking the GRE, insurance licensing exams, and others.

After checking that my pockets were empty and inspecting my eyeglasses to make sure there were no cheating devices installed, a testing center employee directed me through a metal detector into a hallway of room after room filled with computers. Each room had a separate proctor outside monitoring an array of camera feeds, and each feed corresponded to an individual workstation in the room. My testing room was at the end of the hall.

Like the other exams being administered that day, the Series 65 is computer-based. The proctor for my room let me in, directed me to an open station, and showed me how to start my test. From there, I had three hours to complete the exam.

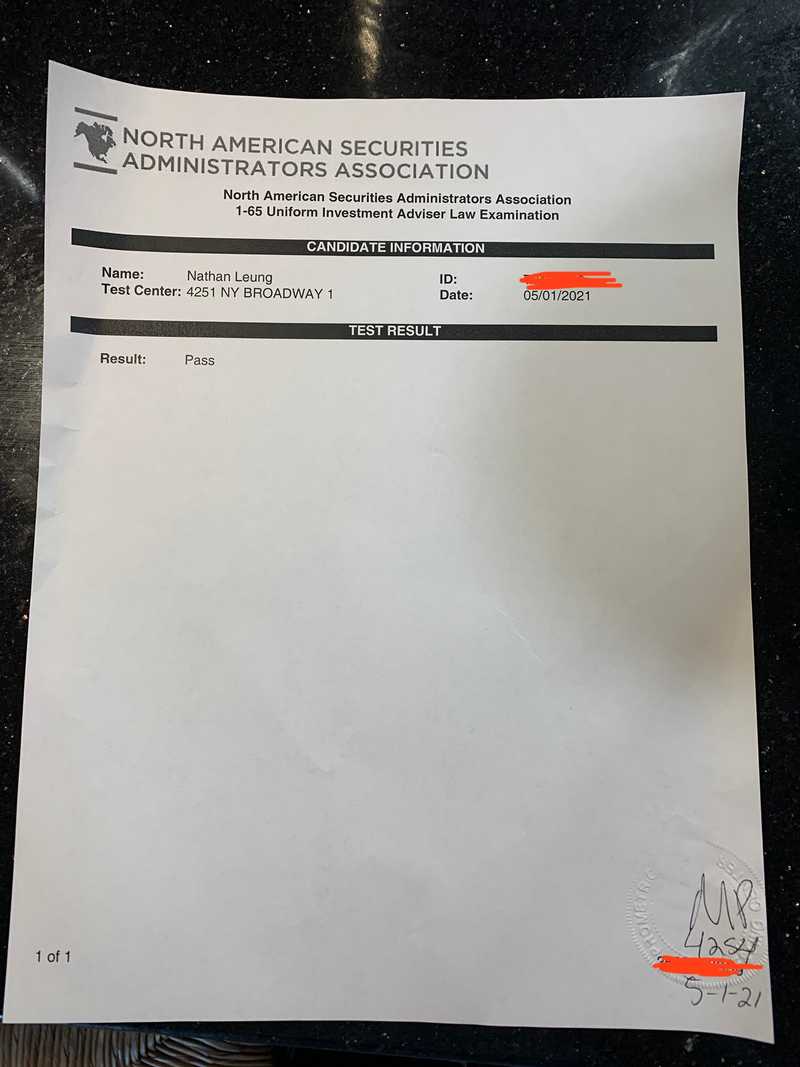

Feeling confident based on my passing scores on my practice exams from earlier in the week, I ended up finishing the test in just about two hours. My result was shown as soon as I clicked the final submit button.

I passed!

Three takeaways after taking the exam:

- The Kaplan practice exams accurately simulated the real exam, and doubling down on reviewing the topics Kaplan said I was weak in — like the Uniform Securities Act and investment adviser representative legislation in general — probably increased my likelihood of passing significantly. Reflecting on my study schedule as a whole, focusing on the legal and compliance aspects of the exam seemed to yield the most gain for the least effort (although this is likely because I was already pretty familiar with the purely financial topics on the test).

- Despite my initial hesitation, I now think getting the Kaplan test bank is very much worth it. In addition to knowing exactly which areas I needed to improve on, taking simulated practice exams made me feel more confident going into test day which improved my general exam day experience and probably helped my score a little bit as well. Consider paying for a subscription once and splitting a login if you’re studying with a group.

- The exam relies heavily on memorization. Had I not been distracted by other things, I think I could have grinded Kaplan for a few weeks and gotten all of this done much faster. In fact, the person I borrowed the Kaplan subscription from did all of their studying in one single week before taking their exam (they passed too).

II. Becoming a Licensed Investment Adviser Representative

Passing the exam was just the first step — for full accreditation, I also needed to become a licensed investment adviser representative.

Every investment adviser representative must be a part of an investment adviser firm, so there are two parts to this:

- Registering an investment adviser firm

- Registering myself as an investment adviser representative of the firm

Investment advisers can register either at the state level, with the securities administrator of each individual state they practice in, or federally, with the SEC. Smaller advisers, with less than $90 million in assets under management, are generally required to register with individual states. Firms become eligible for SEC registration once they have over $100 million in assets under management.

Right off the bat, SEC registration seemed easier to me since each state has different rules and regulations and there are more resources online about the SEC’s requirements than individual states’ requirements. I was also already more familiar with SEC requirements through my studying for the exam, since the test has questions about SEC rules but not necessarily each individual states’ nuances.

Moreover, as someone who travels quite a bit, I didn’t want to have to worry about watching what I was doing because I crossed a state line. Registering with the SEC meant that I could submit one filing and be done2

Technically, even with SEC registration, I also have to submit “notice filings” to each state I plan to practice in, but this entails a single checkbox (the SEC handles the rest) rather than a whole new filing for each individual state.

× Close. Overall, SEC over state registration seemed to significantly reduce the amount of thinking I’d have to do about compliance.

Due to the additional complexity associated with state registration, most [advisers] seek to qualify for SEC registration from the start.

[…]

If the firm is seeking SEC registration, once the agency reviews and approves the firm’s Form ADV, it will declare the firm’s registration effective within approximately 45 days.

By contrast, many states use the initial ADV filing as only the first step in the registration process. After a state reviews and comments on an adviser’s initial Form ADV filing, it will often ask for and review other operational documents, such as a compliance manual or client agreement. A state may even ask an adviser to submit financial statements and require an individual license. Only after all requested documents have been reviewed and approved will a state declare a registration effective. And this process usually takes significantly more than 45 days.

Thompson Hine, “Registering your robo-advisory firm – where and how?”

Unfortunately, as an adviser without $100 million in assets under management, I was not immediately eligible for SEC registration. I found, however, that there was an “internet adviser exemption” for advisers that give advice entirely through the internet. That sounded like an exemption I could qualify for — I would just have to commit to not giving any face-to-face investment advice3

— so I put up a quick website and began filling out the SEC paperwork.

Registering with the SEC

The SEC firm registration forms consist of the fill-in-the-blank Form ADV Part 1, the narrative Form ADV Part 2, and the Form CRS (also known as the ADV Part 3). These forms are filed online at the FINRA Central Registration Depository (CRD), and before I could begin I had to first request access to CRD by filling out a New Organization form on the Investment Adviser Registration Depository (IARD).

What are the parts of Form ADV?

183 words

Part 1 requires information about the investment adviser’s business, ownership, clients, employees, business practices, affiliations, and any disciplinary events of the adviser or its employees. Part 1 is organized in a check-the-box, fill-in-the-blank format. The SEC reviews the information from this part of the form to manage its regulatory and examination programs.

Part 2 requires investment advisers to prepare narrative brochures that include plain English disclosures of the adviser’s business practices, fees, conflicts of interest, and disciplinary information. The brochure is the primary disclosure document for investment advisers and must be delivered to advisory clients.

Part 3, the “relationship summary,” requires SEC-registered investment advisers that offer services to retail investors to prepare a brief plain English summary about the types of services the adviser offers, the fees and costs clients will have to pay for those services, the conflicts of interest the adviser may have, the required standard of conduct, any legal and disciplinary history, key questions to ask the adviser, and references to where clients can find more detailed information about the adviser and the services they offer.

Investor.gov, “Form ADV”

In short, it’s a lot of bureaucracy to navigate and a lot of paperwork to fill out.

Once I got access to CRD, I began filling out the forms.

Since investment adviser registrations are a matter of public record, for Part 1, the check-the-box/fill-in-the-blank form, whenever I was unsure of what to put down, I referred to the public filings of Wealthfront and Compound — two investment adviser startups — to figure out what I should write for my own firm.

For Parts 2 and 3, the SEC gives detailed instructions with specific language to include:

Display on the cover page of your brochure the following statement or other clear and concise language conveying the same information, and identifying the document as a “brochure”:

This brochure provides information about the qualifications and business practices of [your name]. If you have any questions about the contents of this brochure, please contact us at [telephone number and/or email address]. The information in this brochure has not been approved or verified by the United States Securities and Exchange Commission or by any state securities authority. Additional information about [your name] also is available on the SEC’s website at www.adviserinfo.sec.gov.

SEC.gov, “Form ADV Part 2”

To fulfill the requirement quoted above, I literally copied and pasted the statement they gave word-for-word into a Google Doc and filled in my new investment adviser firm’s information, Mad-Lib style.

Drafting the rest of Form ADV Part 2 and ADV Part 3 was similar — all in all, it was a rather mechanical process and I got it mostly done over an hour-and-a-half train ride back to New York after visiting family in Philadelphia.

Once the firm registration forms were complete, I completed my individual investment adviser representative registration. I did this by filling out a Form U4 on FINRA Gateway (yet another website, separate from IARD and CRD). Form U4 had a straightforward, fill-in-the-blank format, and wasn’t overly difficult to figure out.

Finally, I submitted all of the paperwork and paid the associated registration fees. The SEC’s fees added up to $55 — $40 for the firm registration and $15 for the individual registration.

When registering with the SEC, advisers also must send a “notice” filing to any states in which they have a place of business. This is a much easier process than multi-state filing — instead of filling out separate paperwork for each state, the SEC just sends a notice to the selected state securities authorities saying that the firm is registering federally and plans to do business in the state. Unfortunately, notice filing also incurs a fee, and my home state, California, charged $125. So all in all, my initial registration costs added up to $1804

The $15 individual fee is one-time and the $40 (SEC) and $125 (CA) firm fees are annual, so maintaining accreditation in this way will cost my $165/year going forward until I hit the income or net worth thresholds.

× Close.

After submitting a new registration, the SEC is mandated by law to respond within 45 days, and I was pleasantly surprised when I got a response in a little over a week. It came from a real person at the SEC with an @SEC.gov email address, and they responded with very specific deficiencies. I was impressed at how particular they were — here’s an excerpt from one email they sent:

Form CRS Missing Required Information. Form CRS must be formatted and contain all information required by Part 3 of Form ADV. This includes, but is not limited to, specific text, conversation starters, headings, the formatting of certain text, and the order of the information. For example:

- Item 2.B.(iii) required statement of whether advice is limited to affiliated products, limited types of investment, or limited products is missing.

- Item 2.B.(iv) account minimum requirements is missing.

- Item 3.A.(ii) required information regarding other fees and costs is missing.

Each deficiency listed was immediately actionable, and it made it very easy for me to make the changes necessary to get my registration into an approvable state.

Maintaining Compliance

Investment advisory is a heavily regulated industry, so compliance is important. There are a few “optional” registration steps that are good to know in case the SEC comes knocking.

First, the SEC requires a code of ethics for investment advisers. It’s not submitted in the registration process, so you don’t strictly need one, but it’s good to draft one up so you can show it if the need arises. Like I did with the Form ADV Parts 2 and 3, I simply followed the SEC’s instructions and came up with a generic code of ethics that checked all of the SEC’s boxes.

There are also compliance responsibilities with respect to actual investments. I made sure to make it clear in my Form ADV that I do not plan to take control of client funds, and that my firm is only involved in giving advice without actually trading clients’ assets. Essentially, I plan to keep assets under management at $0. This reduces my compliance burden significantly since I don’t have to worry about stuff like providing statements, keeping trade confirmations, etc.

The only meaningful compliance burden I have with the current setup is that I need to remember to file an updating amendment to the SEC every year (and pay the associated filing fees — $40 to the SEC and $125 to California). I don’t plan to make any changes to the current structure, so it should be a straightforward process — essentially submitting a form every January 1st that says “no changes”.

III. Investing as an Accredited Investor

After submitting my final Form ADV revisions, my registration became official on July 22nd, 2021, and with that I became a bona fide accredited investor.

To be completely honest, in practice, this whole process of accreditation — at least right now, for the purposes of startup investing — was sort of unnecessary. As a relatively cash-poor5

College tuition is my biggest expense right now. I didn’t want to sell my stocks, so I’m paying for UCLA with a combination of federal student loans (0% COVID interest rate) and margin from Interactive Brokers (1.6% as of this writing). I’m also trying to pull off some interest rate arbitrage by putting some of the margined funds into a high-yield crypto (USDC) interest account. All this is to say that at the moment, I don’t have much cash left over to invest in startups.

× Closecollege student, I don’t have much investable capital to begin with, and among my friends who are into startups and venture capital, the unspoken secret is that accreditation — at least when investing in individual startups, and especially if the founder is a good friend of yours — is just a box you can check that nobody verifies. The accredited investor rule is designed to protect you, and if you willingly lie to a founder and they take your money, my impression is that there are not many consequences for either side (not legal advice!).

Possessing accreditation is still helpful for more formal investing, such as through AngelList syndicates or on crowdfunding sites like WeFunder6

While crowdfunding sites are by design open to all, accredited investors are able to get access to much higher investment limits.

× Close, since these companies will actually verify your accreditation before letting you invest. Venture capital firms seem to be more strict about verifying accreditation as well. Once I have a steady income again, it will also be nice to be able to put a little bit of money into things I think are cool without worrying about whether I satisfy the financial qualifications for accreditation.

For now, whether I actually end up making a new investment with my accreditation in the next few months or not, I can still get a kick out of sending people the link to my adviser profile on the SEC website, and at the very least I learned something. I came into the process thinking I already had a decent understanding of the markets, and I ended up picking up a whole lot more (especially on the legal side).

In the future, when I do (hopefully) hit the income and net worth thresholds, I also think I’ll be much better positioned to make informed investment decisions than if I had not done this at all. If anything, that might be where I realize my highest returns.

- Another reason why these numbers may seem “low” is that the income and net worth figures were established in 1982 and haven’t been adjusted for inflation since. Making $200,000 per year in 1982 is equivalent to making $560,000 per year in 2021.↩

- Technically, even with SEC registration, I also have to submit “notice filings” to each state I plan to practice in, but this entails a single checkbox (the SEC handles the rest) rather than a whole new filing for each individual state.↩

- Besides a de minimis number of non-internet clients; 15 as of this writing.↩

- The $15 individual fee is one-time and the $40 (SEC) and $125 (CA) firm fees are annual, so maintaining accreditation in this way will cost my $165/year going forward until I hit the income or net worth thresholds.↩

- College tuition is my biggest expense right now. I didn’t want to sell my stocks, so I’m paying for UCLA with a combination of federal student loans (0% COVID interest rate) and margin from Interactive Brokers (1.6% as of this writing). I’m also trying to pull off some interest rate arbitrage by putting some of the margined funds into a high-yield crypto (USDC) interest account. All this is to say that at the moment, I don’t have much cash left over to invest in startups.↩

- While crowdfunding sites are by design open to all, accredited investors are able to get access to much higher investment limits.↩

Recommended Posts

If you liked "Accredited Investor: Investing in Startups With the Series 65", you might also like: